How to apply for a postdoctoral fellowship in ten easy steps

blog fellowshipsFiguring out what to do after your PhD can be stressful. If you’ve not become disillusioned with the world of academia, you’ll probably be looking at a postdoctoral position. There are two real alternatives here: a job as a postdoc on someone else’s grant, or a fellowship.

Fellowships are an exciting option due to the freedom and opportunities they provide, however many simply aren’t aware of the available schemes or how to actually apply for one. This isn’t surprising given the complexities involved in applying for these positions, especially when you’re still relatively new to academia.

I was fortunate to do my PhD at an institution that actively helped early career researchers figure out their next steps and provided guidance on fellowship applications, but I’m probably in the minority here; many universities simply don’t offer this and I suspect that a lack of post-PhD support results in talented researchers being less successful than they otherwise could be.

For this reason, I’ve attempted to put together everything I’ve learnt about applying for a postdoctoral fellowship in the hope that it might be useful for others considering taking this route. This is based on what I’ve learnt from previous applicants, academics who have sat on panels and sponsored applications, and my own experience (I was recently fortunate enough to be awarded a Sir Henry Wellcome Fellowship from the Wellcome Trust, and my stress and confusion during the application process inspired this post). As I’m most familiar with Wellcome’s scheme for junior researchers, this is what I’ll focus on, however a lot of this will be common to fellowships from different funders and at different levels. This is also very UK-centric and based on my experiences in biomedical science (specifically neuroscience) - I’m not sure about options elsewhere but hopefully this information might still be useful!

Step 1. Decide whether the fellowship route is for you

Fellowships aren’t for everyone. The idea of a fellowship is that rather than working as a postdoc on someone else’s grant you get funded to carry out a project of your own design, working with people you choose to work with. For the funders, they’re an opportunity to support talented early career researchers, with the aim of propelling them to academic stardom. A strong fellowship application allows a talented person to work on an exciting project at a world-leading place (these three Ps are the three key ingredients of a good application).

Fellowship schemes are typically competitive, so you need to look pretty good on paper. As is unfortunately typical in academia this means having publications. Having one or two first author papers in “decent” journals should be sufficient here, assuming you’re around the end of your PhD. Evidence of having already been awarded funding (e.g. small grants for research or conferences) is also helpful.

Many people probably self-select out of the process because they don’t feel they’re good enough, even if this isn’t true. This is an easy trap to fall into, especially if you compare yourself with previous awardees who often seem to have superhuman levels of scientific talent. So be optimistic, it’s worth at least chatting to your supervisor to see if they think it’s worth applying.

It’s easy to assume you’re not competitive, don’t fall into the trap of comparing yourself to others as I did

Step 2. Think of a rough project idea

You need to propose a project that will lead to high quality research outputs, but which is also feasible in the time limit. At this stage you don’t need a detailed plan, just an idea of what you’d like to look focus on (for example, a couple of broad primary hypotheses you’d like to test). The project is one of the three Ps I mentioned previously - a good project is necessary for a strong application.

It’s important that this isn’t simply a direct continuation of your PhD work - there needs to be a clear training opportunity, for example learning new analysis methods, as fellowships are intended to foster your development as a researcher.

It’s fine to change field a bit, as long as you can show some continuity from your previous work, and at this stage it doesn’t matter whether your subject of interest aligns with funders’ priorities; this only comes into play at the higher levels, so don’t worry if your chosen subject isn’t “cool” right now.

Bearing in mind the time it takes to complete the whole application process, you probably want to have figured this out about 9 months before the deadline you’re aiming for.

Step 3. Find a fellowship scheme

There are a range of fellowships, which vary in terms of the career stage they’re aimed at and what they offer. Some are fairly generous in terms of duration and funding, while others are fairly brief or will cover just basic salary costs.

There’s sometimes a limit on how many years of postdoc experience is required to apply, even if this isn’t explicit (e.g. the MRC Career Development Award has no requirement, but you’re unlikely to be at the necessary level skills-wise without a few years of postdoc experience).

If you’re applying straight out of PhD, the most obvious choice is therefore the Wellcome Trust’s Sir Henry Wellcome fellowship, which is aimed at those of us at this level and doesn’t require any postdoc experience. There are two rounds per year, with deadlines around May and November, and they seem to award about 15-20 per round (you can view lists of previous awardees here).

Step 4. Identify potential sponsors and talk to them

A fairly crucial step is finding a sponsor(s) who will agree to host you. Most academics will be more than happy to chat with you about your ideas, so don’t be afraid to reach out to them!

Your host institution(s) and lab(s) should be the best place in the world to conduct the research, and you should aim to work with researchers who have a strong track record in the field - the place at which you choose to spend the fellowship is another important ingredient of the fellowship application, alongside the person and project. It’s very strongly encouraged to move away from where you did you PhD – staying within the same institution is likely to be criticised, unless this is clearly the best place for the work to be carried out (examples I’ve seen of this are where the candidate wishes to use a particular dataset or cohort which is based at the institute where they did their PhD).

These fellowships are also very flexible in terms of location, and this means you’re free to spend time at other locations (this was actually a requirement for my application). This is a great opportunity to broaden your horizons, gain new skills, and make contacts outside your host institution, so it’s worth speaking to multiple potential sponsors at this point about collaborations.

Speaking to potential sponsors will also help you refine your ideas for the proposal; they will be able to tell you whether your idea is feasible/actually worth looking at, and might point you in interesting new directions.

Step 5. Write the proposal

Writing a proposal is challenging, and a skill you will most likely not have much experience of at this early stage of your career. I’m not going to go into detail about how exactly this should be done as it could take up thousands of words, but I’ll provide some basic pointers.

It’s virtually impossible to outline a 4 year project in 1500 words. I spent a depressing number of hours rewriting and removing words to get it under the word limit. It’s also tricky to figure out how the proposal should be written – do you go for detail, or keep it more basic so that it makes sense to non-experts? Mine ended up being fairly detail-free, focusing on higher-level aims and hypotheses, but I’ve seen examples of both approaches that have been successful.

You’ll need to cover the background to the project, explain why your research question is important, and provide details of how you’re going to answer the question you’ve set. You’re not expected to have any pilot data, however make sure to reference any relevant work you’ve published already!

Your proposal should leave nothing to the reader’s imagination – make it obvious what question you’re asking and how you’re going to answer it. Make sure it’s clear how you’re going to spend your time, as it’s crucial that your project is obviously achievable in the timeframe – it can be helpful to include a timeline to illustrate this.

Try to contact previous applicants and ask to look at their applications – this is incredibly helpful when you’re figuring out how to structure your own.

Step 6. Rewrite the proposal

As with any piece of writing, getting feedback is invaluable. Your sponsors should be happy to look over the proposal – listen to their feedback, as they most likely have a great deal of experience in grant writing and have almost certainly reviewed grant applications themselves! Ask colleagues/supervisors/anyone who owes you a favour to take a look; Given how short the proposal is, it really needs to be as close to perfect as possible.

It’s also worth pointing out here that the proposal needs to represent your own ideas. Getting feedback from your sponsor is vital, but this shouldn’t be along the lines of “I don’t like your ideas, you should do X, Y, & Z instead”. Not only is this a pretty bad omen for your working relationship, it will also become apparent at interview that the proposal wasn’t your idea.

Getting feedback is crucial. However sometimes it turns out your friends are all too happy to be brutally honest

Step 7. Complete the application

The application requires various other details, such as statements of support from your supervisors/sponsors/mentor. Make sure you ask for these in plenty of time so you’re not left in a last minute panic!

You’ll also need to write a statement about your career to date and how the fellowship would further your career - this is how you address the third key part of the application, the person (you!). This is rather painful as you have to explain why you’re the greatest scientist ever to have lived, despite the fact that most of us seem to suffer from at least some degree of imposter syndrome. The key here is to use your achievements as evidence that you’d be successful if awarded the fellowship and make it clear how the fellowship would put you on the path towards an independent research career. Don’t worry if you’ve not received every award possible, published papers in Science/Nature, and cured cancer by the time you’re finishing your PhD – you might see people who’ve done this, but they’re the exception.

The application form will also ask for publications and awards. It’s fine to include submitted papers here (it’s fairly typical to not have all your PhD work published at this stage), but it’s not worth including work that’s “in preparation”.

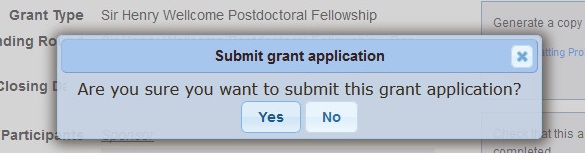

Step 8. Submit the application

Eventually it’ll be time to undertake the terrifying task of submitting the application. Press the submit button and celebrate your hard work with a drink and sudden and terrifying realisation that you’ve not done any actual work for the past month.

Most anxiety-provoking button click of my life

Step 9. Submit the application again

The preliminary application will be reviewed and if you’re lucky you’ll be invited to submit a full application. Roughly half of the applications will be rejected at this stage.

The full application is largely the same as the preliminary application, with various extra bits of information (importantly, the proposal is largely the same at this stage so you don’t need to rewrite this).

You’ll need to speak to the people responsible for research grants at your host institution at this stage as they need to sign off on the submission, and they will probably expect you to do some sort of costing (nothing detailed, this is largely just a formality). Get this done sooner rather than later as you’ll typically only have about a month between hearing back and having to submit the full application.

After you submit the full application it will be sent to about three reviewers, who will provide feedback to the funder. The interview panel will judge whether or not to invite you to interview based on these reviews.

Step 10. Interview

If you’re lucky, you’ll be invited to interview. About half of the full applications will be selected for interview, so well done if you get this far!

The interview is where you’ll be quizzed on your proposal, and if you manage to wow the panel you’ll be awarded the fellowship! Roughly half the candidates interviewed will be offered the money, although this varies year on year.

The interview is worth a guide in itself, so I’ll leave this for now and hopefully address this in the future!

It’s probably pretty obvious now that the whole process is fairly involved. It’s a huge amount of work, and can be pretty stressful. There were multiple occasions where I felt like I had no idea what I was doing, and by the time I got to the interview I was adamant that I would never do this again. However, now I’m free from interview-related stress and panic, it’s obvious that it was 100% worth it.

Even if you’re unsuccessful, it’s a great way to get some experience of grant writing, which will serve you well in any academic career. It also enables you to build relationships with other researchers – if you don’t get awarded the fellowship, you’ve made strong links with your sponsors which could lead to other opportunities (note – these arguments seem entirely unconvincing when you’ve just come out of the interview feeling as though you’ve failed miserably).

I hope this has been helpful to anyone thinking of applying for a fellowship, and good luck!